ThE Dream Builder

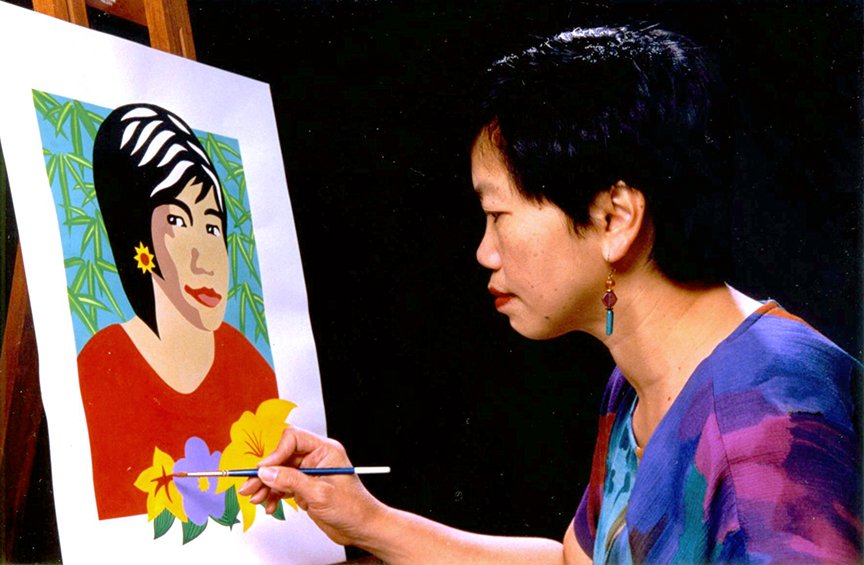

Cantadora “The Dream Builder”

2021 Tempranillo

Shake Ridge Ranch, Amador County AVA

Dedicated to the story and legacy of Nancy Hom.

Nancy Hom chose the Tempranillo from Shake Ridge Ranch as the most reflective of her personal taste in wine and of her story. It doesn’t surprise me once you listen to her rich history in art and living. This wine has the firmest tannins that will age the longest. Their influence can be felt for decades. I often describe this wine as tasting well for up to 50 years and the most likely to maintain its structure intact of any of the wines I create. This feels appropriate given Nancy’s slow and steady ascent in the world of art and her building of a resilient framework of several arts organizations in the City of San Francisco.

Organically farmed by Ann Kraemer

95 cases produced

The silky tannins that this wine will resolve into aren’t so different from the swell of pride Nancy has at seeing her organizations thrive with a new generation of artists and leaders. Mirroring the intricacies of the ever-evolving nature of a wine, the nuances of her story are almost impossible to fit into the length of this essay. In the case of wine, art and life well lived - good things come to those who persist.

“I am both a train and a station,” Nancy says of her life. As a train, she moves fluidly between places, artistic disciplines, and communities. She has seamlessly integrated her artistic activities with her community activism and her spiritual path, connecting people, cultures, and ideas. In the 1970s, at a time when identity, ethnicity, women’s rights, and political issues were being explored, she found commonality with other cultures that have struggled for visibility and social justice. Due to this outlook, her artwork has served a variety of needs across cultures. As a station, she has established deep roots in several communities; and has built many nonprofit startups into the viable entities they are today.

Nancy was born on October 1949, shortly after the communists took over. She spent the first three years of her childhood in a small village in Toisan, a county in the Guangdong province in the Pearl River Delta of Southern China. Her father, facing a life of poverty, had decided as a young man to go to the U.S. for a better life. He found work in a restaurant in New York City. Nancy’s father served in WW2 and did one tour in Normandy. On a trip back home to China, he was introduced to Nancy’s mother by relatives, who arranged their marriage. When he went back to the United States, she was already pregnant. Because of the quota limiting Chinese from coming into the United States, it would be five years after her birth before Nancy would meet her father.

Knowing life would be difficult under communist rule, her parents made a plan to bring the family to the United States. One night Nancy and her mother left with other villagers and walked for a long distance to the border. Nancy says, “I’m guessing that when we reached the shore, we took a boat to Hong Kong. I was only three and don’t remember the details.” She and her mother spent two years in a boarding house in Hong Kong before gaining entry to the United States.

In 1954, Nancy and her mother were finally permitted to go to the U.S. After a long flight, they arrived in New York where friends and relatives greeted them. Nancy met her father for the first time. “It was very awkward. I did not know who these people were and why one of them would call himself my father.” He took them to his tenement apartment on the Lower East Side. There was a bathtub in the kitchen and a small toilet in the living room. This would be her home for the next twenty years.

Nancy’s father waited on tables at a Chinese restaurant six days a week. Her first brother was born when she was seven; the second arrived 10 months later. Her mother worked at home at first, stringing beads into necklaces and bracelets. When the children were old enough to go to school, her mother found work in a sweatshop and her father continued to work long restaurant hours. The children became latch-key kids and Nancy took on the role of caregiver. She walked them home from school and entertained them until her mother came back. They were asleep by the time her father came home.

Eventually Nancy made friends with a few neighborhood kids. Her parents befriended a Chinese couple that owned a laundry across the street. Their daughter was three years older than Nancy and the girls became like sisters. Another girl lived two blocks away in a 2-story private house. The two were inseparable during their puberty years. Nancy and her Chinese friends experienced racism, mostly through name-calling. Once, three white boys threw stones at them and one of them pushed her to the ground. Her elbows still bear faint scars to remind her.

School was difficult for Nancy in the beginning. She didn’t speak the language and was teased by her classmates. Nancy’s first grade teacher couldn’t pronounce her Chinese name, so she called her Nancy. Her parents, wanting her to fit in, didn’t object. She was tracked into the “B” group at school because she was shy and she stuttered when she spoke. Fortunately, in 3rd grade, she found a kind teacher who drew her out of her shell. Eventually she lost the stutter and found her voice and focus.

As the older sister in charge of two young brothers, Nancy would entertain them with cardboard boxes, clothespin dolls, and pots and pans. Life was simple and kept to the confines of their apartment and the surrounding streets. The neighborhood kids would get together and play ball and street games outside. She also loved roller-skating and jumping rope.

Nancy’s father was a humble man who was content with a simple life. On his day off he would cook for the family; then walk the children to a nearby park. Her mother would take her to the village friends’ apartments, where they would reminisce about China. Thanks to a few relatives, who took them to Chinatown and to amusement parks, the children were able to venture outside their neighborhood. Nancy’s father helped other immigrants from China settle into the neighborhood. This was the community that Nancy and her family belonged to. They survived by supporting each other.

Nancy’s 6th grade teacher taught art to the students. Although she was not aware of it at the time, that was the start of Nancy’s lifelong interest in art. She was recommended to the art class in Junior High School and upon graduation, she applied to the art program at Washington Irving High School. Her teachers encouraged her to apply to an art college. From 1968-1971 she attended Pratt Institute, paying for it with scholarships, loans, and savings. Unable to afford the dorm, she lived at home all four years.

Nancy’s journalism teacher at Pratt encouraged her to join the school’s weekly newspaper, the Prattler. All the editorial copy had to be done by Wednesday, laid out on Thursday, set into linotype and printed by Friday, then distributed by Saturday morning. This grueling schedule occupied most of her weekends while on weekdays she took the regular art courses. Nancy moved through the ranks of editorships to become the Editor-in-Chief of the paper by her senior year. 1968-1972 was a rich time in news events. The newspaper covered the student body’s reaction to the MLK Assassination, Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement and the Woman’s Rights Movement, among other pivotal events. Her experience gave her a foundation in activism that she would merge with her art career throughout her life.

In her senior year, Nancy was deeply moved by a concert given by Joanne (Nobuko) Miyamoto and Chris Iijima on campus. Until these Asian American activist/songwriters performed, Nancy was not sure what to do after college. But when she heard them sing of the Asian American experience, including songs about Chinese waiters and laundrymen, she knew she wanted to be part of the nascent Asian American movement. After graduating from Pratt with a BA in Visual Communications, Nancy joined Chickens Come Home to Roost, a collective on the Upper West Side that Chris and Joanne belonged to. There, Nancy met her future husband Bob, a budding photographer and filmmaker. With a few others also interested in media, they formed the Asian Media Collective to document the activities of the Asian American Movement. Along with Joanne and others, she was also a founding member of Asian Women United, a group that got together to discuss concerns specific to Asian American women.

During the day Nancy worked at a publishing company. Her evenings and weekends were steeped in meetings, study groups, and anti-war efforts, but her main activity was creating films and slide shows for both the Asian Media Collective and Asian Women United. A 3-month trip to Asia interrupted her work, but opened her eyes to a world larger than Manhattan. She traveled to Hong Kong, Japan, and Taiwan. On her way back she met activist groups in Hawaii, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Nancy reflects, “The values I learned from those early movement years informed my choices for the rest of my life.”

When she returned home from Asia, she continued her activity with the Asian Media Collective but some members were leaving the group. Bob was thinking of moving to California. Nancy was ready for a change, too. Knowing that her parents would be upset if she just left the family, Nancy suggested to him that they get married. In 1974, after a whirlwind marriage, they piled everything they owned into Bob’s Saab and drove to California. They first lived with friends in a rented place in Los Altos Hills, but after a few months decided to move to San Francisco.

In San Francisco, Bob and Nancy had heard of an arts workshop at the International Hotel (I-Hotel). By the time Nancy joined Kearny Street Workshop (KSW), it had already been active for two years and was running a series of workshops for the community. In 1974, KSW rented a large storefront on the Jackson Street side of the I-Hotel for exhibitions and performances. Co-founder Jim Dong had designed a mural on the side of the building and Nancy went down to help paint it. She became part of the KSW scene and the I-Hotel struggle for low-income housing.

The I-Hotel was the last vestige of a thriving Filipino American enclave that was home to many farmworkers, merchant marines, and service workers. Various community organizations occupied the ground floor, including KSW. For over nine years, the mostly elderly tenants faced threats of eviction but community protest prevented it from happening. Besides documenting rallies and marches, KSW’s role in the efforts to save the building was to focus on the tenants, who were the heart of the struggle.

At KSW Nancy found her creative outlet, whether through teaching drawing, attending the poetry workshop, taking classes, curating an exhibition, or presenting a program on stage. The exhibitions attracted students and like-minded artists from all over the Bay Area. This exciting hub of creativity and networking ended abruptly on August 4th, 1977, when KSW and other storefronts were evicted along with the tenants upstairs. The police, carrying batons and riding horses, came at 3am and brutally evicted everyone despite a 3,000-member human shield that surrounded the Hotel. Nancy and other members guarded the Workshop but by 5am the I-Hotel was fully evacuated. Reeling from the displacement, KSW was not able to fully continue the classes and community events. It would remain nomadic for many years, using other venues to produce and present art. In 1981 KSW premiered the Asian American Jazz Festival, which ran successfully for 17 years under the artistic direction of Mark Izu.

In the late 1970s, Nancy was hired by the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA) to be the curator-at large for San Francisco’s five new neighborhood cultural centers. After assisting at various centers, she was stationed at the Western Addition Cultural Center, curating shows primarily for the Black American community. “Being curator-at-large through the CETA program introduced me to so many different cultures,” she says. She developed relationships that broadened the scope of her career as a community artist. Her husband, also a CETA employee, was an apprentice photographer at the De Young Museum. Tired of rent increases, they bought a little house right before the program ended.

After the I-Hotel eviction, Nancy continued her silkscreen printing, working with many trailblazers to advertise cultural events and causes. Through poster-making, she was able to express her love of dance, music, community, and also her outrage at injustices. She participated in poster projects at Japantown Art and Media Workshop and exhibited in group shows. She also created posters at Somarts Cultural Center and began taking assignments from groups that needed low cost advertisement. Nancy agreed to do them provided she had free reign on the design. In 1983 Nancy and Bob’s daughter Nicole was born.

Life was a challenge for the new family in their daughter’s early years. Bob rented a photo studio and launched a career as a freelance photographer. Nancy continued her art and community service. The two of them shared parenting duties. Despite their artistic successes, the couple was always worried about their next paycheck. As mother of a young child, she could not work fulltime. By 1987, after Nicole entered kindergarten, work started to pick up again.

Although she loved the medium, silkscreen printing was very difficult for her. She found it arduous to pull the ink across the screen multiple times. When she heard that Mission Grafica, a silkscreen facility, had acquired a machine that pulled the ink automatically, she immediately went there. Mission Grafica was a creative hub for a diverse group of artists, including international stars, and there were always exciting exchanges among them. Being in the Mission also gave Nancy a chance to further her ties with Galeria de la Raza, another arts organization serving the Chicano and Latin community in the neighborhood. There, she met muralists, silkscreen artists, and visionaries who asked her to be part of their projects.

In 1989, Nancy started working with Children’s Book Press and illustrated books, including the award-winning “Nine-in-One, Grr! Grr!,” a Hmong folktale. She went on to become a freelance designer for Children’s Book Press for several years. At the same time, Nancy started attending meetings with the Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA), an organization founded in 1989 by Betty Kano, Flo Oy Wong, and Moira Roth for Asian women artists to network, to present their work, and to advocate for more visibility. Nancy’s long engagement with AAWAA includes exhibiting as an artist as well as serving as an arts consultant and board member. She guided the organization in strategic planning and development. In 2003, she helped AAWAA transition into a nonprofit organization by forming a mock board and having it conduct itself as a 501(c)3 for a year until it received the official status. Nancy has had a symbiotic relationship with AAWAA and to this day feels indebted to the organization.

In 1995, Nancy was thrust into an unexpected role as director of Kearny Street Workshop, a position she held for almost nine years. Despite its long history, KSW did not become a formal 501(c)3 until Nancy took office. Although the Asian American Jazz Festival was still going strong, most of the old KSW members had left. Nancy had to rebuild the organization in order to ensure its continuance. She took a crash course in leadership, gave up her studio and much of her art-making, and paid herself a 1/4 time salary. She moved KSW to South Park, a fashionable mecca for multi-media artists and formed relationships with other community groups within and beyond the Asian American community. KSW grew into an organization with a vast network of APA participants and supporters. It presented several groundbreaking projects under Nancy’s leadership.

Nancy feels that her lasting legacy was KSW-Next and its showcase festival, APAture, A Window on the Art of Young Asian Pacific Americans, intended for ages 18-30. In 1998 there were no venues for young APA artists to meet and show their work. KSW-Next launched APAture in 1999. The multi-disciplinary event, curated and planned by the young artists themselves, provided a forum for that age group. The KSW-Next program ensured a renewing supply of human resources to KSW and also to the arts field.

Nancy stepped down as KSW’s director in 2003, right after she secured a 3-year grant that guaranteed a full time salary for the next director, which she herself never had. Today, KSW is vibrant and APAture continues Nancy’s intention of having an annual showcase for a new generation of APA artists. She still maintains ties with her longtime organization. After leaving KSW, Nancy used her knowledge of grant writing and organizational development to assist other organizations, including AAWAA, Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center, Manilatown Heritage Foundation, and the Euphrat Museum of Art.

After the I-Hotel was razed in 1978, community pressure prevented anything from being built for 27 years until the site was finally sold to the SF Archdiocese of the Catholic Church. Chinatown Community Development Center developed the building into 104 units of senior housing and community space. In 2005 a new I-Hotel was built. Nancy curated exhibits and presented events at Manilatown Center for five years; then went back to her art-making. Manilatown Center continues to be a place where seniors, artists, writers, and the community can meet and see presentations, listen to music, or take classes.

In 2010, Nancy transitioned from her silkscreen work to 3-D installations and sculptures. She was able to pursue this new path with the help of AAWAA and other organizations she supported. After creating a few installations and sculptures, she settled on the mandala as her main medium. “I have created dozens of mandalas since 2012; they range in size from 2.5-ft to 12-ft in diameter. The mandala can tell a story, celebrate a community, and educate the public on issues. Its impermanent nature lends itself to reflections on adaptation and change. Sometimes I involve the community in making some of the items.”

When she was in her early 60s, Nancy was a weekly presence in various dance nightclubs in the Mission and in the Fillmore. A big fan of blues, jazz, and Latin music, she went to concerts and supported local musicians. She befriended Christine Harris, the director of the Jazz Heritage Center In the Fillmore. Christine exhibited her work and asked her to create several exhibitions on black jazz musicians. Nancy obliged and also helped other arts presenters that she met there.

After the clubs were gone and the Fillmore community had scattered, Nancy concentrated on her mandala-making. A minor stroke in 2015 and a car accident in 2017 slowed her activities, but not for long. Her daughter got married and moved to Sacramento. In 2019, Nancy’s granddaughter was born; her grandson 3-1/2 years later. She takes time to revel in her grandchildren’s lives but stays committed to her community work. Since the pandemic began in 2020, Nancy, a Tibetan Buddhist, has maintained an ongoing mandala to say daily prayers for the deceased. The mandala contains deities and mantras. She changes the names each week. Saying prayers is her way of helping the community heal from grief. Ever evolving, she is also developing other talents, such as writing articles and making mandala projections.

Nancy feels that the four pillars of her life – art, community, activism, and spirituality – are converging. I can see that she is perpetually focused on community, using her creativity skills to heal and uplift others and help them build their dreams. There is no better way to immortalize her work than “The Dream Builder.” I only hope this wine, even with its long potential, can keep up with the woman it honors.